Npe Peopel Love Art Museums but Has the Art Itself Become Irrelevant

In 1971 the performance artist Chris Burden stood against the wall of a California fine art gallery and ordered a friend to shoot him through the arm. That .22 burglarize shot was the opening salvo of a move that came to be chosen "endurance fine art"—an unnerving species of performance art in which the performer deliberately subjects himself to pain, deprivation, or extreme tedium. Try as he might, Burden never quite matched the shock of his spectacular debut (and he did try, once letting himself be crucified onto the dorsum of a Volkswagen Protrude).

As fate would accept information technology, I had but shown my students at Williams College the grainy footage of Burden's shooting when we learned of his death in May. Curiously, the prune did not provoke them as it had their predecessors in my classrooms in decades past. No one expressed any palpable sense of daze or revulsion, let lone the idea that the proper response to the violation of a taboo is honest outrage. One student fretted nigh the legal liability of the shooter; another intelligently placed the work in historical context and related it to anxiety over the Vietnam War.

Placing things in context is what contemporary students do best. What they do non do is approximate. Instead there was the same frozen polite reserve one observes in the faces of those attending an unfamiliar religious service—the expression that says, I have no say in this. This refusal to guess or accept offense can exist taken as a positive sign, suggesting tolerance and broadmindedness.

But there is a broadmindedness so roomy that it is indistinguishable from indifference, and it is lethal. For while the fine arts can survive a hostile or ignorant public, or even a fanatically prudish one, they cannot long survive an indifferent one. And that is the nature of the nowadays Western response to fine art, visual and otherwise: indifference.

In terms of quantifiable data—prices spent on paintings and photographs and sculptures, visitors accommodated and funds raised and square footage created at museums—the picture could hardly be rosier. On May i, New York's Whitney Museum moved from 75th Street to the Meatpacking District and reopened in a $422 meg edifice. The move first seemed inexplicable when information technology was announced several years ago, simply it has proved to be a bright stroke. Relocating to a hotter and more fashionable neighborhood abutting the wildly pop High Line Park is i of those gambits that instantly transforms the logic of the game board, similar castling in chess. The new Whitney was designed by the furiously prolific Renzo Pianoforte, and while it will non please everyone (its boxy hinge of platforms distressingly recalls the flight tower of an shipping carrier), it swaggers with brio and brio and is fast condign ane of the world'southward best-attended museums.

Every bit robust is the art market, to approximate by a Christie'due south sale on May 11 that set several records, including the highest price ever paid at auction for a piece of work of art: $179.4 million, paid by an anonymous applicant, for Picasso'south Women of Algiers (Version O). One tin can wait more such record-breaking in the next few years every bit the art market is increasingly roiled past Hong Kong dollars, Swiss francs, and Qatari riyals. (The heir-apparent of the Picasso was subsequently revealed to be the former prime minister of Qatar.)

But quantifiable data tin just describe the fiscal health of the fine arts, not their cultural health. Here the picture is not so rosy. A bones familiarity with the ideas of the leading artists and architects is no longer part of the essential cultural equipment of an informed denizen. Fifty years ago, educated people could be expected to identify the likes of Saul Bellow, Buckminster Fuller, and Jackson Pollock. Today ane is expected to know most the human being genome and the debate over global warming, just nobody is idea ignorant for being unable to identify the builder of the Freedom Belfry or name a unmarried winner of the Tate Prize (permit lonely call up the name of the almost recent winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature).

The last time that artists were part of the national chat was a generation ago, in 1990. This was the year of the NEA 4, artists whose grants were withdrawn by the National Endowment for the Arts considering of the obscene content of their work. Their names were Tim Miller, John Fleck, Holly Hughes, and Karen Finley—the latter especially famous because her nearly notable work largely involved smearing her own body with chocolate. As it happened, their work was rather less offensive than that of Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe, who had been the field of study of NEA-funded exhibitions the year before. Serrano's photo of a crucifix immersed in a jar of his own urine was chosen "Piss Christ." Mapplethorpe'south notorious self-portrait featured a bullwhip thrust into his key aperture. Even the New York Times, a stalwart champion of Mapplethorpe, could non honestly describe that photograph, let lone publish information technology, referring to it with coy primness every bit a "sadomasochistic cocky-portrait (nearly naked, with bullwhip)."

That controversy concluded with a double defeat. In a case that was heard by the Supreme Court, the NEA Four failed to have their grants restored. Just Senator Jesse Helms and Representative Newt Gingrich besides failed in their determined effort to defund the NEA (total budget at the time: $165 1000000). And the American public—left with an impressionistic vision in which urine, bullwhips, and a naked simply chocolate-streaked Karen Finley figured largely—drew the fatal conclusion that contemporary art had nothing to offer them. Fatal, considering the moment the public disengages itself collectively from art, fifty-fifty to refrain from criticizing it, art becomes irrelevant.

This essay proposes that such a disengagement has already taken place, and that its consequences are dire. The fine arts and the performing arts take indeed ceased to matter in Western civilization, other than in honorific or pecuniary terms, and they no longer shape in meaningful ways our prototype of ourselves or define our collective values. This collapse in the prestige and consequence of art is the central cultural phenomenon of our mean solar day.

It began a century ago.

For most of man history, works of visual art were the direct expression of the society that made them. The artist was not an autonomous creator; he worked at the behest of his patron, making objects that expressed in visible course that patron's beliefs and aspirations. As club inverse, its chief patrons changed—from medieval bishop to absolutist autocrat to captain of industry—and fine art changed forth with it. Such is patronage, the mechanism by which the hopes, values, and fears of a society make themselves visible in art. When World War I broke out in 1914, that mechanism was delivered a accident from which it never quite recovered. If human feel is the raw material of fine art, here was material aplenty merely of the sort that few patrons would choose to await upon.

When I went to Germany to report architecture in 1980, it was still mutual to see wounded veterans from both earth wars. The first seats on buses or subways were reserved for them and were usually occupied. One day a boyfriend pupil and fellow history buff chanced to remark that the worst cases were from World War I, just of course one never saw them.

"They never testify their faces?" I asked, naively.

"Mike," he said, "they have no faces to show."

He was speaking of the Verstümmelten—the mutilated, those who lost jaws, cheeks, and noses in the shambles of the trenches, where a raised caput was the target of option. They had been so wounded, brought to a nearby field lazaretto and put together as much every bit possible, that they would spend the residual of their lives seen only past the family members who tended to them. "There is one," my friend said—I can still picture the expansive gesture he fabricated—"in practically every street."

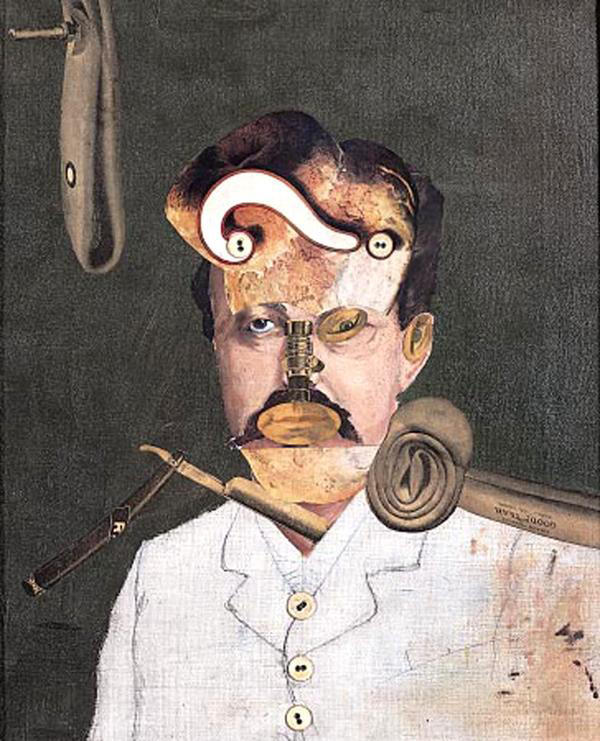

Not until then did I properly grasp the unbearable intensity of German language artists such as Ernst Kirchner, Otto Dix, and George Grosz, who created their nigh memorable work during the state of war or just afterward. The human trunk—dynamic, beautiful, created in God'southward epitome—had long been the central discipline of Western art. It was now depicted in the most tormented and fragmented manner, every coil of innards laid blank with obscenely morbid imagination. Kirchner and Dix depicted the gore. Grosz, who refrained from showing actual injuries, was even more disturbing. He made collages of faces out of awkwardly assembled parts, like a jigsaw puzzle assembled with the wrong pieces, suggesting those sad prosthetics that would accept been an ubiquitous presence in 1918.

Christianity had introduced the motif of beautiful suffering, in which even the most agonizing of deaths could exist shown to have a tragic dignity. But things had at present been washed to the human body that were unprecedented, and on an unprecedented scale. The brutal savagery of this art can be understood simply as the product of commonage trauma, like the blubbering of absurd free associations that tumble from our mouths when in a state of shock. That kind of irrational expression was the guiding principle of Dada, the motility that came most at the end of the war and that was made famous by Marcel Duchamp's celebrated urinal turned upside down and named Fountain. Even the name Dada itself was a quintessential absurdist functioning, selected at random from a French-German dictionary (the word is French baby talk for "hobby-horse").

Dada applied unserious means to a serious stop: the search for an creative linguistic communication capable of expressing the monstrous scale and nature of the war. But the absurdist moment was short-lived and quickly superseded. The toppling of Europe's three main empires and the Russian Revolution seemed to confirm that the W had entered into a radical new phase of cultural history, the most consequential since the ascension of Renaissance humanism half a millennium ago. There was a full general sense that a earth radically transformed by war required an equally radical new art—an art of urgent gravity. While modernistic art had certainly existed before the state of war, there now came into being a comprehensive "modern movement" that was active in all spheres of homo activeness, non just in art but in politics and science also. In its wake, Pablo Picasso rose from being a mere painter with a quirky personal fashion to a world-historical figure whose piece of work was as important to the future of mankind equally Einstein's or Freud'due south.

All this gave the modernism of the 1920s its tone of moral seriousness, which became even more serious once the Slap-up Depression began. 1 sees this high-minded seriousness most strikingly in the architects of the modern movement. They saw their mandate equally the solving of the central architectural challenge of modern life—how to use new materials and ways of construction to make housing affordable and cities humane. Today the lofty principles that motivated them seem quaint, such equally that German language fixation on the Existenzminimum. This was the notion that in the design of housing, i must first precisely calculate the absolute minimum of necessary space (the acceptable clearance between sink and stove, between bed and dresser, etc.), derive a floor plan from those calculations, and then build as many units as possible. I could not add a unmarried inch of grace room, for once that inch was multiplied through a 1000 apartments, a family would exist deprived of a decent home. Then went the moral logic.

We may shudder at the thought of so many identical families penned into and then many identical boxes, but at root this idea was an expression of a humane and humanistic view of the earth. It took for granted that the mission of compages was to improve the man condition, even as modernistic artists causeless that theirs was to express that status. To accomplish this, they did not require the traditional patron. The prestige and power of those patrons had been macerated by the state of war, and with that diminution went their ability to dictate to artists. That became even more pronounced after the stock-market collapse in the tardily 1920s, especially in the U.s.a.. When the Museum of Modern Art introduced European modern architecture to America in its celebrated 1932 exhibition of the International Style, it dismissed the traditional capitalist client with remarkable highhandedness. A half century of robust creative and architectural patronage by the industrialists who had ruled American life since the Golden Age was written off with a sneer by the exhibition's organizer, Alfred Barr: "Nosotros are asked to take seriously the architectural taste of real-estate speculators, renting agents, and mortgage brokers." In other words, the making of art was far as well serious to be left to sentimental clients who might mistakenly want a narrative painting with a clear moral message, or a facsimile of a villa they had admired in Tuscany.

Afterwards World War II and the introduction of the cantlet bomb, it seemed pointless to try to preserve the confused traditions of a civilization that had brought the world to the ledge of oblivion. Instead, the artists came to believe they had to dispense with the unabridged accumulated storehouse of artistic memory and the history of the benighted W in order to brainstorm afresh.

The 1950s painter Barnett Newman summarized this line of thought pretentiously but accurately:

We are freeing ourselves of the impediments of memory, association, nostalgia, fable, myth, or what take you, that have been the devices of western European painting. Instead of making "cathedrals" out of Christ, human being, or "life," we are making information technology out of ourselves, out of our ain feelings.

"We are making information technology out of ourselves" is a fair summary of the revolution in patronage the modern move had brought about, in which the creative person himself had now been transformed into his ain patron. And withal, radical as were Newman'south existentialist "zero" paintings, consisting of spare, massive vertical stripes smoldering like a cosmic portal about to open, they remained traditional in one key respect: They still existed in a recognizable moral universe. For all their portentous grandiloquence, the nada paintings yet speak of that aboriginal durable strand in the Western tradition, a belief in the tragic dignity of man.

With the irreversible decline of that belief, it may be said that the historic period of postmodernism began, and that the journeying to the present state of monumental public indifference to art started to accelerate.

Susan Sontag's 1964 essay "Notes on 'Camp'" is the commencement endeavor to define the rapid alter in attitude that was taking place in the early 1960s toward art, society, tradition, everything. It was not and then much a change in style or philosophy equally in sensibility. This new sensibility, Sontag wrote, "sees everything in quotation marks" and "converts the serious into the frivolous." Although the condition of the world seemed ever more serious—the Cuban Missile Crisis had just taken place—a younger generation in the Western democracies had adamant that the proper response was to exist even less serious, to throw up ane's hands and face the earth with irony. Even as Sontag wrote, that new sensibility was being reflected in painting (Andy Warhol), sculpture (Claes Oldenburg), and architecture (Robert Venturi), each of whose works exist, in some sense, in quotation marks. Mutual to all was a shared posture of irreverence and ironic detachment. This new impunity worked itself through the veins and arteries of the art world with remarkable briskness from studio to gallery to museum to classroom. In 1 respect, the insouciance of pop fine art came as a refreshing cakewalk. Warhol'southward soup cans and Oldenburg's behemothic floppy hamburgers fabricated no momentous claims to accept banished nostalgia, legend, and myth; though in part they were intended to reveal the hollowness of capitalist commercial culture, they could non help but offering subject field thing that was attractive, reassuring, and familiar. These were the nevertheless lifes of prosperous postwar America, and, like their 19th-century counterparts with their glistening fruit and vegetables, they spoke of abundance.

Only in architecture did the new sensibility take a while to establish itself. What client would wish to invest their millions in an "ironic statement"? The Quaker sponsors of Guild House, a retirement habitation in Philadelphia, were chagrined to acquire that the metallic sculpture over the entrance was meant to represent a giant television antenna—in the words of its architect Robert Venturi, "a symbol of the anile, who spend and so much time looking at Boob tube." Unimpressed past his claim that it was inspired by the Château d'Anet, they promptly had it removed.

In the same way that popular art was meant as criticism withal featured a welcome annotation of playfulness, postmodern compages did offering a playful, witty alternative to a modernism grown dried and formulaic. The calamitous failure of urban renewal was now everywhere credible, and modernism's claim that information technology could create humane cities was exploded definitively in Jane Jacobs'due south brilliant The Death and Life of Bully American Cities (1961). Later on a fourth dimension, postmodernism'due south jaunty irony was carried into the American cityscape by commercial clients such as AT&T who built the first uninhibitedly witty skyscrapers since the art deco towers of the Roaring Twenties. The burden fine art had carried since the stop of Earth War I—the obligation to express ponderous things in ponderous ways, the burden to exist on perpetual baby-sit duty in the advanced, ever alarm to any reactionary tendency—had been cast off.

For the nearly function, though, this new nonchalance was short-lived. Oldenburg's goofy seven-foot Floor Burger (1962) was pleasantly apolitical. But a mere 7 years later, he would produce the most memorable item of antiwar art to come out of the Vietnam War, Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks, a parody of a tank he erected in front of Yale Academy'due south administration building. Instead of a gun turret in a higher place its treads, it sported an oversized lipstick, not proudly erect but distressingly flaccid (Oldenburg's sardonic commentary on masculinity and war). Although it was removed within a yr (to be replaced after by an inferior replica in permanent materials), Lipstick was a harbinger of the return of seriousness to the art scene, a seriousness at present tinged with fury, indignation, and, increasingly, politics.

A whole spectrum of other political causes soon plant expression in fine art—environmentalism, feminism, Chicano rights. This new seriousness differed sharply from the quondam. If modernism had understood itself to exist upholding and developing the culture from within, revolutionizing Western art in society to save information technology, its postmodern successors offered a critique from without. This was the counterculture that emerged after the collapse of the postwar liberal consensus, and its opinion was essentially adversarial, distinguished by hostility to the existing order. Information technology viewed the advanced industrial order of the West non as the highest development of human civilization only rather every bit a corrupt enterprise whose shameful legacy was slavery, colonialism, and exploitation.

Information technology is easy to meet why an artistic civilisation unwilling to champion even the abstruse concept of Western culture would feel resentful toward a modernism that sought to practise just that and would try to cut it downwardly to size. Indeed, a canard was widely disseminated that abstract expressionism—the least political of all art movements in its rejection of the politicized social realism of the 1930s, which found its most indelible expression in Jackson Pollock's drip paintings—was itself a CIA plot. According to this deranged view, the Congress for Cultural Freedom had sponsored international exhibitions of artists such as Pollock and Willem de Kooning as part of a CIA-subsidized entrada of cultural imperialism. While this highly tendentious reading of history has been roundly discredited, it has passed into the conventional professional wisdom.

Nigh of this slipped nether the radar of the American public, which had by the 1970s established a kind of concordat with the fine art world. Any art had to offer—minimalism, conceptualism, photorealism—was a zany precinct where anything might happen, a source of entertainment, a zone that might exist safely regarded with beneficial neglect. There was no arguing with success: When confronted with something every bit willfully bizarre every bit one of Robert Rauschenberg's Combines (wherein a blimp Angora goat might exist inserted through an motorcar tire), the public was happy to say "don't ask, don't tell" and tiptoe away with a smile on its commonage face. Later on all, Rauschenberg was very famous, and his fine art made him very rich. If yous didn't like it, fine; somebody would and would pay huge sums for it.

Such was the concordat that fell apart spectacularly in the late 1980s, and when it did, artists were but every bit shocked equally the public.

From time to time, so-called conceptual artists had looked to find new ways to use the human body artistically. Their agenda was by no means to express humanist values or fifty-fifty beautiful suffering—quite the reverse. In 1961, Piero Manzoni offered for sale 90 tin cans purportedly containing the Merda d'artista (to this twenty-four hour period it is uncertain whether or not the cans really contain his excrement, since to open up one would cost on the order of $100,000). Manzoni's foray into scatology was a prophecy of things to come. Ten years later, Vito Acconci became a minor celebrity with his performance of Seedbed, which involved his hiding nether a platform in a gallery and speaking to visitors higher up while masturbating.

If these acts had any political agenda at all, it was anarchy. Merely in the wake of Roe v. Wade and and then the AIDS epidemic, the human body assumed a political significance it had not had since abstract expressionism had banished life-drawing every bit ane of those "devices of Western European art" that Barnett Newman had condemned. Now, as Barbara Kruger proclaimed in the historic poster she designed for a 1989 abortion-rights rally, "Your torso is a battlefield."

In that location poured forth a great deal of trunk-centered fine art. Its one peachy constant was a high quotient of rage—equally furious equally any statue-smashing interlude in the long history of iconoclasm. Here was an anguish and loathing not seen since the days of Grosz and Dix, both of the self-hating multifariousness (expressed through masochistic acts) and generalized rage against society (Serrano'south urine-immersed crucifix). I think of Ron Athey's now notorious Four Scenes from a Harsh Life, for which he incised patterns into the back of a collaborator with a scalpel, dabbing up the blood with paper towels that were affixed to a clothesline and swung out over the wincing audition.

Such art, different that of Grosz, offered no coordinates from which society could navigate to find a higher purpose. Rather, it fulfilled the definition of what the belatedly Philip Rieff called a "deathwork," a work of art that poses "an all-out assault upon something vital to the established culture."

Given this fine art's flagrantly, deliberately transgressive nature, it is remarkable how surprised and bewildered its creators were when they felt the full measure of public disapproval, which came to a climax with the effort to defund the National Endowment for the Arts. After all, having been properly vetted and feted at every footstep by curators and journalists, academics and bureaucrats, these artists quite reasonably assumed that they were across reproach. That there was yet another role player out there in the mists, a public upon whose judgment their fate might depend—a public that might act to withdraw state funding of projects that were expressly intended to transgress its values—seems not to have crossed their minds.

Ane Harvard scholar suggested that Serrano erred because while he knew "his photograph to be provocative, he did not count on such a broad audition outside the art world." Just what to make of an artist who does not wish to have a broad audition or speak to his own society? At a minimum, it is non even political fine art—fine art that seeks to persuade or focus attending—if it exists only within the silo of its ain echo bedroom.

Although the torso-art move lost its incandescent fury as the AIDS crisis subsided, at that place lingered a fascination with the degraded human body. This reconfigured itself in the 1990s as the movement known as "abject art," which the website of London's Tate Gallery tactfully defines equally "artworks which explore themes that transgress and threaten our sense of cleanliness and propriety particularly referencing the body and bodily functions." The most notorious instance came seven years ago when a Yale art student presented a performance of "repeated self-induced miscarriages." According to her own account, she inseminated herself with sperm from voluntary donors, "from the 9th to the 15th day of my menstrual cycle…so every bit to insure the possibility of fertilization," later on using "an herbal abortifacient" to induce the desired miscarriage. Here was indeed a deathwork, proud and unashamed. (The only solace is that she might non, in the end, have actually carried out her project in reality.)

Such projects, existent or imaginary, returned the spotlight to the human being trunk. But this was hardly the body that was, equally Hamlet put information technology, "like a god in apprehension." Rather, information technology was a ravaged and wounded matter, degraded and caught. One can about understand the popularity of the ghastly flayed and "plastinated" bodies exhibited by Günther von Hagen, the notorious corpse artist, in his traveling "Body Worlds" exhibition.1 Different the degraded victimhood on display in nearly examples of abject fine art, his figures evoked dynamic action and freedom, and at least a shard of hope.

When viewed against this dispiriting backdrop, poor punctured and perforated Chris Burden seems similar an Old Principal.

And yet, and yet. Even as the public was flinching from the excesses of functioning art and abject art, it was embracing museums every bit never before. The newly opened Whitney is the last of New York'due south four major museums to renovate, enlarge, or replace its abode in recent years. It reflects a worldwide tendency that began in 1997 with the about simultaneous openings of the Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which fabricated overnight celebrities of their architects (Richard Meier and Frank Gehry, respectively).

Bilbao had another, more consequential effect. In just three years, information technology famously recouped the toll of its structure (which was underwritten by the provincial Basque government) partially through admissions but generally through increased tourist revenue. This was dubbed "the Bilbao upshot," the notion that the edifice of a prestige museum tin can transform

the international profile of a city and make it a pilgrimage destination.

This helped launch a feverish moving ridge of international museum-building that still shows no sign of abating. In fact, the only thing remotely like information technology is the cathedral-edifice boom of the Isle de France in the 13th century, when each city vied to build the loftiest, thinnest, and brightest Gothic nave.

If i compares the performance of museums to other amusement facilities in the United States in terms of box part, the museums come off splendidly. According to the American Association of Museums, almanac omnipresence hovers at about 700 or 800 million, and it did non even endure declines during the recession of 2008. These figures far exceed the combined attendance at major-league sporting events and entertainment parks. This is not by accident, for museums have been assiduously cultivating their attendance for quite some time. The process began with the "Treasures of Tutankhamen" exhibition that opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1978 and drew a record 1.8 1000000 visitors. Startled museum trustees, previously accepted to covering the almanac deficit with a discreet check, took notice of the lines stretching around the block. The temptation proved irresistible, and the culture of the museum reoriented itself toward the regular production of a reliable blockbuster.

By whatsoever mensurate, in that location is inappreciably an institution in the Western globe then salubrious equally the museum today. By any measure—at that place's the rub. For some things cannot be measured but are important even so. In 1998, exactly twenty years afterward the Tutankhamen exhibition, the Guggenheim brought along "The Art of the Motorcycle," an exhibition widely panned as without educational merit. Yet it, too, was a crowd-pleasing awareness, and it, also, broke omnipresence records. At that place may be a considerable difference betwixt the gold mask of Rex Tut and a Harley-Davidson Sportster motorcycle, but not in the calculus of quantifiable information by which museums judge their success. Still, it did not seem to trouble the general public that fine art museums now sported motorcycles and helicopters (in the entrance hall of the Museum of Modern Art), for they no longer expected museums to offer objects only an feel. The temple of the arts had been transformed into what the critic Jerry Saltz has called "a revved-upwards showcase of the new, the now, the next, an always-activated market of events and experiences, many of which lack whatsoever reason to exist other than to occupy the museum manufacture."

Nor was the academy willing to draw any helpful distinction between King Tut and the Harley-Davidson, certainly not on the basis of aesthetic quality. To merits that the mask of Tut was in some style superior— to privilege it, in bookish jargon—required making aesthetic or historical determinations that scholars were increasingly unwilling to brand. For a generation they had been schooled by those French 20th-century intellectuals Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida who said that art and literature were best understood as expressions of a structure of power. Improve to eliminate altogether the word fine art, which evokes unhappy images of dominant cultures expressing their hegemony, in favor of the aesthetically neutral term visual culture, which makes no judgments about merit but merely looks at the purposes for which i makes works of fine art—or, in their terms, "objects of visual interest." Thus with no articulate directive from society to stress the adept, museums have by default chosen to stress the new. The Met's most successful exhibit over the past x years was a display of loftier-couture dresses by Alexander McQueen, a way designer who had hanged himself in his London apartment a yr earlier.

Southurely, such a large category of human achievement every bit the fine arts cannot only become irrelevant and cease to thing. Or can it? In his prophetic essay "The Prevention of Literature," George Orwell speculated that literature might one day be bedridden by totalitarian regimes' enforcement of intellectual conformity. The writing of imaginative prose demands an unfettered intellect, something incompatible with political orthodoxy of whatever stripe:

Prose literature every bit we know it is the product of rationalism, of the Protestant centuries, of the democratic individual. And the devastation of intellectual liberty cripples the journalist, the sociological writer, the historian, the novelist, the critic, and the poet, in that order. In the future it is possible that a new kind of literature, not involving individual feeling or truthful ascertainment, may arise, but no such matter is now imaginable. It seems much likelier that if the liberal culture that nosotros accept lived in since the Renaissance comes to an cease, the literary fine art will perish with it.

It seems absurd to predict that the novel itself might ane twenty-four hours become extinct, and yet Orwell was right to connect its heyday to the "Protestant centuries." From Defoe and Fielding to Austen and Dickens, the stuff of the novel was the account of finding i's place in the world—either through union, choice of profession, or journey of inner growth. In feudal Europe, however, one's place in the world was fixed. Before the novel could come into existence, the specific course of the individual life had to become a thing of interest, and for this to happen, the feudal order had to fall.

Orwell recognized that the novel, like any genre of art, is the product of a detail cultural moment. Each genre reflects certain systems of belief and social structures, and it will flourish with them or shrivel accordingly. At the end of the Middle Ages, passion plays and manuscript illumination withered away; presently thereafter, the Renaissance courtroom conjured up opera and ballet. This was the last cracking comprehensive reconfiguration of artistic genres, which has left u.s. with the formal hierarchy in which the triad of painting, sculpture, and architecture represents the nigh prestigious and significant of the arts. These were the primary arts concerned with the making and adorning of palaces and churches, and the trends they codified soon worked their fashion down through the decorative arts—ceramics, textiles, and the like. And they maintain their inherited prestige, although the footing beneath their feet has changed dramatically.

Nigh recently, the great shakeup in the hierarchy of art genres came nearly through technological innovations. The first major new artistic genres to ascend since the age of the absolutist courtroom, photography and the movement picture, are its products. (Peradventure digital art in some class will become the defining new genre of this century, or it might in the end be more of import as a ways of transmission, like the phonograph record.) These new technologies do not merely add to the repertoire of existing genres, expanding choice in the great human boutique of entertainment and expression. They too affect the relative position of all other genres, all of which are in competition with 1 another, for consumers as well equally for talented producers.

A new applied science tin change the cultural moment with shocking speed. America'southward civilisation of vaudeville, vibrant for a one-half century, sank into oblivion after the introduction of sound in motion picture in 1927. Fred Allen, one vaudeville performer who found a lifeboat in radio, observed with chagrin how theater chains promptly began to pecker motion pictures above their vaudeville programs. The large bands of the Swing Era and their culture of nightclubs and ballrooms could not survive television. Now it is literary culture that is on the chopping block. According to Publishers Weekly, the greatest sales of nonfiction books was achieved in 2007—the same year (the magazine might have noted) that Apple introduced the iPhone. Since then, book sales take been declining steadily, upwardly to x percent a year.

Just engineering lone cannot explain what has happened to the fine arts in the past few generations.

The same period has witnessed a catastrophic breakup of the belief systems that sustained Western civilization. The conventionalities in its goodness and fundamental virtue, once the unspoken premise on which society operated, is something that any high school student, properly instructed, knows how to debunk. The word civilization is endangered, equally shown by Google'south Ngram, which tracks the frequency of discussion usage in print. Afterward 1961, civilization began to exist used less and less; by the mid-1980s, its usage had dropped by half. At that very moment, the ironic usage of the discussion "civilization" started to rise sharply. As Sontag predicted, everything could exist put into quotation marks. Equally goes the word, so goes the concept.

Without a sincere concept of the meaning of civilization, one cannot explicate why a masterpiece of Egyptian New Kingdom art counts for more than than a creation of 1960s industrial design (other than in dollar value). If one cannot practice even that, it is difficult to see how one might set out to make serious and lasting art. To brand such art—art that refracts the world back to people in some meaningful way, and that illuminates homo nature with sympathy and insight—it is not necessary to be a religious believer. Michelangelo certainly was; Leonardo da Vinci certainly was not. But it is necessary to take some sort of larger organisation of conventionalities, a larger construction of continuity that permits works of art to speak across time. Without such a belief system, all that one tin hope for is short-term gain, in the coin of glory or notoriety, if not actual coins.

If fine art is merely the expression of a construction of power, then to dislodge it from its traditional position of prestige in the public square would exist a liberation. It would exist a similar liberation to dispense with the whole trove of traditional civilization—public rituals, folk songs, patriotic fables and myths, truthful holidays (as opposed to days off from piece of work)—that from the vantage of Foucault might be viewed equally oppressive instruments. And indeed they have been largely swept away. But their place has been taken by the institutions of mass media, commerce, and ad, which exist for the present, are unable to speak across time, and are at present occupying much of the terrain formerly held past traditional civilisation and fine fine art.

Architecture is the 1 fine art that cannot beget to alienate its public—it but costs as well much to build something, and and so the architect must still please his sponsor to get his piece of work washed—but information technology, too, has suffered by losing its sense of historical continuity. Equally information technology has done and then, it approaches the state of advertising—big, eye-communicable, memorable objects created by glory designers with a signature style. It is no coincidence that when this began to happen, some fourth dimension in the 1980s, architects stopped working to resolve their buildings—meaning, they ceased their labors over the details and minor features of program and elevation that would ensure that a building's parts expressed in miniature the order of the whole. Architects such as Wright and Louis Kahn did not know about DNA when they designed their greatest works—but they understood the principle that the logic of the whole was embedded even in its tiniest element. Virtually no architect does this anymore (apart from a few Japanese masters), and it would be pointless to practice so.

The final irony is that the contemporary museum edifice, the colossal works of freeform sculpture past celebrity designers, may be the only lasting work of art produced in our age. For the making of a slap-up building was one time akin to making a fine musical instrument; today the job more nearly resembles the making of a successful billboard.

For a generation or more, the American public has been thoroughly alienated from the life of the fine arts while, paradoxically, continuing to relish museums for the sake of sensation and spectacle, much as information technology enjoyed circuses a century ago. The public accepts that it has nothing of import to say well-nigh who we are, though it does occasionally rouse itself when something is at stake that does reflect our collective values. When Daniel Libeskind proposed rebuilding the World Merchandise Heart in the academically stylish deconstructivist style, the public outcry resulted in his being replaced and the construction of a sober and dignified belfry. A like outcry has delayed the building of Frank Gehry'south perversely anti-heroic memorial to Dwight D. Eisenhower, which might yet exist realized (never underestimate the ability of bureaucratic stealth). But these are exceptions to the pattern of a dormant and indifferent public.

This estrangement has been a disaster for the arts, which demand to describe inspiration from the society and civilisation that is its substrate. Information technology is a myth that an art withdrawn from the realm of public inspection and disapproval is a freer and superior art. The impulse to evade censure can inspire raptures of ingenuity. (The passage of the prim Hays Code in 1932, which led to four decades of censorship in Hollywood, increased the sophistication and wit of American films by a magnitude.) We hear much about art enriching the human experience, which is an agreeable platitude. But information technology is the other way round. The human feel is needed to enrich art, and without a meaningful living connection to the society that nurtures it, art is a plucked flower.

Chris Burden could never repeat the stunt that made him famous, for the trick about breaking taboos is that you can practice it simply once. Subsequently that, all you can practice is incessantly reenact the breaking long after the taboos have gone.

And all that remains is what is broken.

1 I wrote well-nigh this exhibition in "Body and Soul" in Commentary'south January 2007 issue.

richardsonvatint64.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.commentary.org/articles/michael-lewis/how-art-became-irrelevant/

0 Response to "Npe Peopel Love Art Museums but Has the Art Itself Become Irrelevant"

Post a Comment